On March 25, 2017 the adorably-named Thoughtful Dog magazine published my short story, The Temple of Great Virtue:

The full name of the place was 1 Night 1980 Hostel Tokyo, the entrance on a clean backstreet two dozen blocks north of Ueno Station. Elsewhere, the areas of Ginza, Roppongi and Shibuya were flaring up, gardens of light and taut gushes of activity, but their vivacity didn’t reach this far. As evening settled in, life bowed and retreated inside, leaving the bright sentry-like vending machines the lone observers of the two girls (or were they women now?) circling the building in search of the hostel’s sign: “1980” in black on a glowing white square. The salaryman’s colors.

Kira dug her fingers into the shoelaces and then the heels of her sneakers, stepping out of them into the economical lobby, too small to complete a full cartwheel in. Clarissa followed suit, eyes flicking to Kira for cues. The girl (Kira wouldn’t call her a woman) behind the counter stood up and the Japanese greeting Kira intended to say emerged in English, to align with the straight brown hair parted dead center and the not quite American accent. This would have been Kira’s first chance to exhibit her language skills in front of Clarissa, a demonstration of how different a world this was from the tri-state area and how necessary Kira was, but no matter. There would be ample opportunity. It was enough that Clarissa was eyeballing with trepidation the ticket machine that loomed in front of the check-in desk.

“Where are you from?” Kira asked, though the girl was probably as sick of that question as she was.

The girl’s wan smile, the way she didn’t look up from their registration forms as she replied, “Canada,” confirmed this.

“But I’ve lived here a long time,” she added, as though by emphasis alone she could more fully fasten herself to Japan, loosen the roots of Canada from the soil of her identity.

“How long?” Kira asked, curious and friendly, an expat herself.

“Five or six years,” the Canadian said, her face a theatrical struggle to recall the number.

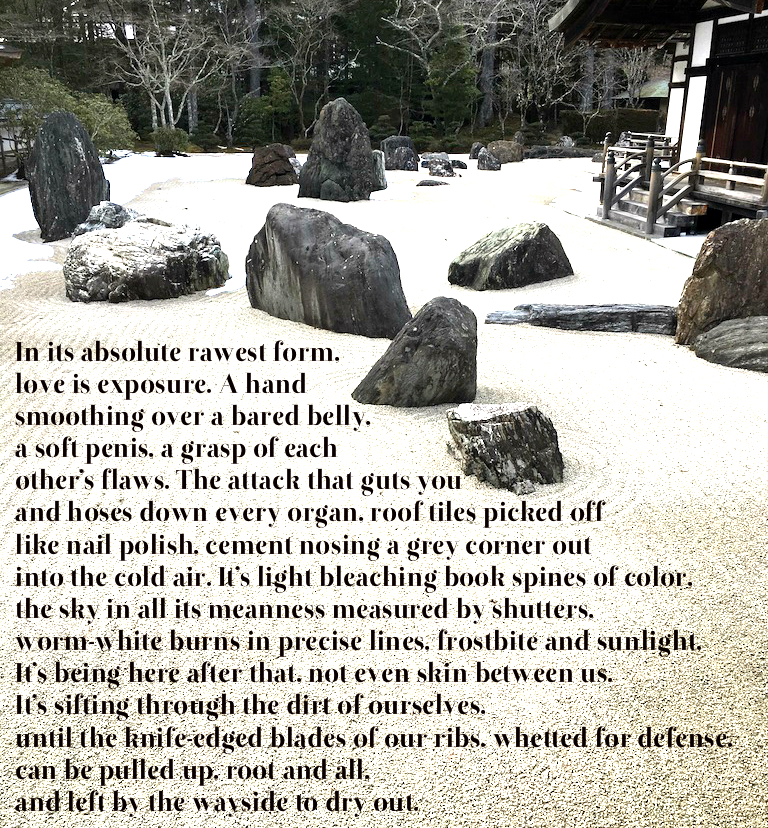

Kinkaku-ji, Kyoto

Kira had lived in Singapore for nearly as long, but didn’t say so. She handed over her passport and wondered if the Canadian realized yet that Japan was not a country prone to adopting its admirers, that she would be forever spoken to in broken English and permitted to make social blunders the Japanese would eviscerate one another for, that her stint here was cute but would always be considered temporary.

“Why are American passports so garish?” The Canadian asked with a snicker, holding Clarissa’s open at the full color photo and the illustration of a bald eagle.

Clarissa didn’t laugh, but Kira did and pulled out her other passport.

“At least the photo is better than the Irish one. Black and white. Like a creepy mug shot.”

They had to pay cash, the Canadian said, disengaging from her check-in booth to identify the appropriate buttons – raised and analog, marked with room types and number of nights, which clicked pleasantly when pushed. But first they would each need to feed the ticket machine ¥6400. Clarissa goggled at Kira. She had forgotten to exchange her dollars at the airport, had assumed she could do that anywhere. As though Tokyo were Disneyland, a series of smooth paths lined with entertainment and convenience in equal measure. Kira shrugged, offered to cover them both, but then found she was short. As the Canadian explained with impatience that a 7-Eleven two blocks over had an ATM, Kira inserted seven ¥1000 bills and retrieved her tickets and change. The Canadian looked askance when Kira handed over a ticket for a big towel along with the one for the room.

“You don’t need the big towel. You get one as part of your amenities kit. You get a fresh towel, body wash, toothbrush, etc, every day.”

“Everyone?” Kira asked.

“It’s only for female guests.”

“Why?” Clarissa asked. “That seems sexist.”

“It’s not sexist. Most of our guests are male, so it’s an incentive to encourage women to stay here. But I can’t check you in until you’ve both paid,” she said with a huff.

They walked through the quiet, humid streets, getting lost almost immediately as Clarissa hadn’t listened to more than the beginning of the instructions. Kira hadn’t listened at all. She hailed a passing businessman in his fifties, who was quintessentially accommodating and pointed them in the right direction. Kira picked over the magazine rack, chanting dumbass in her mind, happily unhelpful as Clarissa realized she would need to overdraft her account. In response to her comment on how silly it was that her $200 was useless, Kira said nothing.

At 28, Kira felt barely adult. It was a role she could assume but which retained the sensation of a memorized act. However, next to Clarissa, three weeks her senior, Kira’s adulthood shone with authenticity. Despite a yearlong boyfriend, Clarissa still exuded the air of a virgin, stammering in surprise when Kira told her they would need to be naked at the hot springs in Hakone. It was a challenge to imagine Clarissa having sex, but unfathomable to envision her attempting seduction. Clarissa still opened her mouth and let burps out at will, unaware that following with an “Excuse me” did nothing to cancel out the disgust that pricked at Kira (and, Kira presumed, others).

“You see her, what, once a year for a lunch when you’re in the States. I don’t see why she deserves ten days all of a sudden,” Eóin had reproached when Kira admitted to reconfiguring her week solo in Japan to accommodate Clarissa’s proposed joint vacation. “At most, she deserves a weekend. What has she ever given you?”

The question resurfaced in Kira’s mind as they made their way back, Clarissa celebrating every correct turn with excited yips.

“I think you’re one of the only people I know who walks faster or at least on par with me,” Clarissa said.

“Huh,” Kira replied, out of breath from keeping stride with Clarissa’s gait, which approached a run and rendered the living, foreign streets mere scenery.

But that’s how their friendship had gone since freshmen year: Clarissa oozing over the depths of their closeness and similarity of feeling, while the grit and texture of who Kira really was vanished in Clarissa’s watercolor portrait of her.

Back in paper slippers in the grey lobby, they obtained Clarissa’s ticket and then waited with amenity kits in hand. A vending machine was wedged between the reception desk and the elevator.

“Gerolsteiner,” Kira laughed, pointing out the bottles. “My German friend used to import that stuff and drink only that because she thought the water in Singapore made her hair fall out. It’s horrible.”

The Canadian leaned back in the check-in booth.

“So bad,” she agreed.

“And my friend would make me drink it every single time I went to her place.”

The Canadian rolled her eyes. Kira suspected that they could become friends, considered inviting her out for a drink.

The sixth floor was: ‘Women’s floor only. The violator will be prosecuted.’ The moderate space had been divided into slivers of hallways and the compact capsules they were to sleep in, each with only a curtain for privacy. Farts would be shared. Their closets lined one hallway, their bunks another. The toilets were in one room (unlocked), the showers in another (locked). The ritual activities, performed alone in a certain order, were to be uncoupled and rearranged and coordinated with others. The sleeping room smelled, a mix of socks and mustiness, as though the few windows hadn’t been opened since the hostel’s namesake year. Kira accepted it, knew she could put up with it for a few nights.

They dropped off their things and returned downstairs with their sneakers in plastic bags. The Canadian had come around her desk to demand in firm English that a huge red-cheeked Chinese woman remove her shoes at the door. The woman wheezed, baffled, mumbling about the bag she had left here earlier. Kira and Clarissa ducked around them as the Canadian, zealous as any convert, advanced on the woman to insist again that she take off her shoes. Tottering with her heels hanging out, Kira remembered that they had to hand over their closet keys before leaving. She held hers out to the Canadian, who scowled and took the crumpled plastic bag. The key hit the floor with a bounce and Kira scooped it up.

“Oh,” the Canadian said, taking the key.

But Kira knew it was too late. She had been relegated to the class of guests who mistreated the Canadian, and now ranked among the locals who tittered at the Canadian for acting Japanese and the drunk men who tried to wheedle their way onto the sixth floor. Kira doubted the Canadian had a procedure for appeals, even if the misinterpretation was hers, and the possibility of friendship extinguished into smoke.

Akihabara’s ice white fluorescents only drove Clarissa’s jetlag in deeper, so dinner was quick, with Kira doing most of the talking around their bowls of udon noodles. When they returned to the hostel, the Canadian replied to their calls of goodnight with a tight-lipped smile. For the remainder of their few days in Tokyo, she was absent, her place at reception taken by a languid Japanese man. Kira was once again stuck with Clarissa on an island of English, where Clarissa seemed to suck up all the resources, spraying her conception of Japan over the living country. It fascinated Kira how Clarissa was incapable of eliminating herself from her observations. Everything was made relevant and relative. It was bearable though. Kira’s relish at Tokyo’s familiar bustle, its brisk autumn stride, plus the afternoons she begged for herself, all countered Clarissa’s disbelief that an Asian country could be so similar and yet different to what she knew.

“They have women-only subway cars? Why?”

“Well, you’ve seen the crush of the commutes. Some men use that to grab a free handful.”

“Wait. Really? But the Japanese are so quiet and polite.”

“You really think what you see is all there is?”

“Of course not,” Clarissa defended, producing the right response without bothering to examine it deeper.

The parks and gardens Kira had fastidiously starred on Google Maps were a pleasant and disappointing green. Kira wanted to propel the friendly, lingering summer out the door and bask in the chilly, fiery solitude of fall, which was in its adolescence, the trees only just gilded around the edges or bejeweled with a few leaves the color of pomegranate arils. By peppering Kira with questions on Japan, Clarissa attempted to mask her impatience as they strolled. A nice patch of green was not Instagram-worthy. Hakone was though. The mountains, thrusting up around a cold blue lake marked by enormous red torii [1] were festooned with a few bolts of orange, the maples and oaks. But most of the landscape was still drawing in the deep breath that preceded the aria of color to come in November.

In Singapore, placid in unending equatorial heat, Kira was starved of seasonal shifts, the adagio of trees. Her frustration clawed at her ribcage, pulled at the corners of her mouth. Not only had she been robbed of the release of autumn but she had to endure Clarissa’s repeating, “It’s so pretty. It’s so beautiful. Look at how pretty the water is.”

It turned out they wouldn’t have time to visit an onsen, for which Kira was grateful. Observing Clarissa fuss and fret over stripping nude, as though her naked body was anything of gravity or note, would have been exhausting.

“Do you think you’ll ever live in Japan again?” Clarissa asked on the bullet train to Kyoto, reeling Kira out of her book.

“I wouldn’t mind it, obviously. But Eóin’s job is the main factor that determines where we live, so.”

“It’s still so weird that you’re married.”

Kira and Eóin had been married four and a half years.

“I’m still so sorry that I couldn’t come to the wedding,” Clarissa continued. “But, you know my friend Kristen’s wedding was literally the day before, so there was no way I’d have been able to fly to Ireland in time, and I couldn’t not go to Kristen’s wedding because she’s been like my best friend since third grade and I was one of her bridesmaids. I would have been her maid of honor but she has a sister, so, duh it went to her.”

Kira, who had heard this several times in the past, nodded and allowed her gaze to sink back to her novel.

“Oh my god, did you ever see the photos from Kristen’s wedding? Did I show them to you already?”

“I saw a few on Facebook a while ago,” Kira replied with reluctance.

“It was so beautiful. It was held in—”

As Clarissa retrieved the photo album on her phone and rattled off as many details as came to her mind about the wedding of a person Kira had never met, Kira gave an audible sigh. That and her still-open book ought to have been sign enough, but it wasn’t. Kira wrote off the rest of the train ride. At least she had another can of Kirin Chuhai Lemon STRONG, even if it was a bit warm by now. It seemed impossible to Kira that Clarissa had never deduced that their burgeoning camaraderie had stuttered to a halt by second semester of freshmen year. Kira had confessed to a long struggle with depression and Clarissa had stated that she didn’t believe depression was real. Kira hadn’t been angry at the time; she had been charmed, glad her friend’s emotions were too shallow and sun-warmed for oil spills. The anger came later, as Kira observed that she was being replaced by a watercolor of herself, and it rotted through the entire foundation of what Clarissa perceived as a solid friendship.

It was Kinkaku-ji [2] that broke it, cleaved it with a resonant split. Both halves were held in place only by the decreasing pressure of Kira’s grip. Dulled but still gaudy under a moist grey summer sky, the temple was cosseted by polluted streams of tourists, busload by busload quickening the tide and thickening the crowd around the shining, gold leaf-slathered, must-see sight that Kira had seen four times, most recently a year ago. And because of Clarissa she had once again paid the over-priced entry fee to be honked at by Chinese men, bumped aside by bulky Americans, and trampled by classes of Japanese schoolchildren in identical hats – in short, she had been demoted to a white tourist in a country she had explored, studied and lived in on and off for two decades. It all grated against her skin, breaking her open and making a mess. Her fingernails scored pink moons into her elbows.

“I see what you mean about it being touristy but also something you have to see,” Clarissa commented in between chomps of Pocky. “There’s a museum we could walk to that’s fifteen minutes from here.”

Kira could barely speak. Her irritation shot out of her in jagged arrows. The Insho Domoto Museum of Fine Arts was an egoistical several floors that Insho had designed and devoted to himself, but his work was lovely enough that Kira could forgive him. What she couldn’t forgive was Clarissa’s compulsion to slap the label ‘beautiful’ over every painting, scroll and sculpture, as though she had qualified the pieces and put each in its box, dumbing down the elegance, complexity, technique and history to a trite word. The urge to lash out was battering Kira’s bones. A sticky oil well pushed up under her skin, seeping through the seams frayed and torn. She planted herself in front of the massive strokes of black calligraphy, soaking in its ink and movement too long for Clarissa’s interest.

See? Kira wanted to say. There are things you cannot see that I can. Important things. Gorgeous things. Have you figured out yet how limited you are?

Creation. That was what the character meant, but the literal definition was only part of its soul. Kira’s eyes flooded and spilled over, a jittery laugh lodged in her lungs. She wanted to peel herself, pare down to Creation alone, slop over the floor, leap up and dance in an ardent attempt to perform Creation, the inky core that suffocated and birthed and screamed and breathed, was clean-edged and roughly ended, the sun setting and rising in the same movement, the orgasmic terror-knowledge that even as you paint Creation, you are finishing it. You will cease to create. Have you figured out yet how limited you are?

Kira made raw excuses to Clarissa and escaped into an afternoon she had claimed for her own. Honeyed sun lathered the streets in thirsty light and she just about fell into the cool quiet of Daitoku-ji [3], a Buddhist complex of temples, halls and tea houses too somber and entrenched in history for the busloads of tourists. She sought out the shelter of Zuihou-in [4], curling up in front of the Zen rock garden she had fallen in love with in college, which last year Eóin had declared the most beautiful place he had ever seen. Eóin was often puzzled by Kira’s compass of emotions, her infatuation with the feel of a place, her swooning over the colonial elegance of the Raffles Hotel as well as the writhing, plucky sprawl of Kathmandu. He appraised a location on utility, efficiency, potential. Beauty had moved him to words only a handful of times in their seven year relationship. Kira would die before exposing such a place to Clarissa’s cheap, freely given approval.

There was the breeze and the leaves, the clack of the wooden memorial boards in the ancient cemetery. Kyoto and all it meant to visitors, UNESCO, Instagram was held at a distance. Kira sat for an hour with the coarse sea of stones, the sharp rocks and vivid moss overlaid with shadow and sun. It was barely enough. Decision made, she unfolded her stiff legs, trembled out of the temple grounds and into a convenience store for several cans of Kirin, drinking one on the way back to the hostel, gulping down the rest as she charged through maps, cross-referenced Shinkansen stops with kōyō [5] destinations, and pinned down Sendai with a thump of her heart. She booked herself a hotel, not a hostel, and packed like a thief frightened of being caught.

At 5:30pm, Kira sat at a wooden table in the warm, ground floor café. They had planned to meet at 6:00. Kira picked up half a pint of amber ale, Kyoto-brewed, and drank in nervous sips, her torrential pulse begging her to leave the speech she had typed out on her phone and memorized as a note instead. There was still time. She could still get out. Clarissa would be mean. She would have every right to be mean. With measured breaths, Kira hardened and steeled herself for reproach, fury, accusations of impossible selfishness and broken promises. Alcohol unfocused her gaze and her mind whipped up retorts and defenses, polished an arsenal. Clarissa’s flippancy about mental health. Her revolting burps. Her smothering subjectivity. How delicious it would be to smack Clarissa with the truth that Kira had never intended to invite her to the wedding and that only the coincidental timing of Kristen’s had prevented this fictional friendship from concluding then.

Clarissa skipped in, five minutes early, and launched into a summary of her afternoon even before she plopped down at the table, blind to Kira’s anxiety and to her suitcase. Kira let her talk. She was reminded of the last day of spring break freshmen year. Clarissa was supposed to drive them both back to Boston University, but she had been late and so Kira was fortuitously still home when her family received the news. When Kira called, Clarissa answered the phone with a deluge of excuses and recounted in extensive detail the errands she had completed and had yet to complete before she could pick Kira up. It was several minutes before Clarissa realized Kira had been repeating her name and Kira was able to tell her that her grandfather had died that day; she wouldn’t need the ride to Boston.

Finally, Clarissa finished replaying her every step and the thoughts that accompanied them, and asked how Kira was.

“Not great, honestly.”

“Why? What’s wrong?”

“I need to be honest,” Kira began, as planned. She was aware her words sounded practiced but she didn’t care. “I originally booked a trip to Japan to take some time for myself and I thought that traveling with you while taking a few hours to myself every day would be enough, but it’s not. I feel like you may have noticed that I’ve been getting more frayed and impatient, which is not your fault. I’ve been overextending myself for months now. I had fun exploring Tokyo with you, but I now need to head out and be on my own for the remainder of my time here. You’ve gotten the hang of how the trains and things work, so I really believe you’ll be fine. Here is the itinerary I put together for Osaka and the details for our hotel reservation. It’s too late for me to cancel, but this should cover my half.”

Clarissa watched her stutter through this speech with a steady, dark gaze that flicked to the documents and ¥10,000 note for a mere instant.

“Wow. Okay. Are you sure? I mean… Is there any way we can make this work? Like, you could take more of the day to yourself and we could meet at dinner?”

Kira shook her head, eyes sopping. The noise of the café swelled with accented English, anonymous extroversion, the smell of beer and reheated croissants.

“Okay,” Clarissa said softly. “Can I hang out with you while you pack?”

Kira gestured to the suitcase and Clarissa’s disappointment betrayed her dashed hopes of talking Kira out of it. Every moment this conversation went on was physical agony for Kira. Air was cotton in her mouth. Her stomach jerked back and forth. Escape. Escape. Escape.

“I’m, uh, going to catch the 6:55pm back to Tokyo,” Kira said, rising unsteadily.

“Can I hug you goodbye?”

“Of course,” Kira said with a wet laugh, jumpy that the lash of anger hadn’t appeared and waiting for it still.

“It’s okay,” Clarissa murmured, pulling back to look Kira in the face. “I understand. It’s important that you take care of yourself. This isn’t the end of our friendship. Who knows? It might even be good for me to travel around on my own too.”

Shame burned Kira’s cheeks. With a duck of her head, she said thank you and goodbye and good luck, and stepped out into the velvety Japanese night. Her face screwed up with tears, she walked to the wrong bus stop, but refused to retrace her steps across the bright, lit window of the hostel café. Kira would switch to the right bus at the next stop, rather than risk Clarissa spotting her, thinking Kira had changed her mind and rushing out, delighted. For Kira to correct that misconception was to illustrate her own incompetence, at directions and as a friend, and embarrass them both. Though that sloppy, ugly scene was avoided, humiliation dogged Kira through Gion, awash in shops and shoppers, and sat with her on her suitcase on the platform at Kyoto Station, the trains delayed in a nation where tourists will tell you the trains are never delayed.

Safe in the speeding Shinkansen at last, Kira felt soaked through. The dark windows offered only her reflection cut through by the occasional strip of town. Clarissa’s kindness had gutted her, though Kira was so grateful for her understanding. But the joy of being rid of her was irrepressible. Kira was happy now, relieved, and she knew that made her awful. She was proud she hadn’t apologized.

She spent the night in Tokyo, explored museums in silence the following morning, and then hurtled herself north, far from the haven of English. Her cheeks pinking in the October sun, she gorged on the cascades of red orange perfect yellow green racing over the valleys and mountains of Tohoku, all of it gushingly alive on the brink of barrenness. A firm step up would have sent her soaring. Kira laughed out loud, submerged in a wooded trail taken at her own pace. Isolated and clarified in the landscape of a country she knew and loved and knew would never belong to her, ‘Creation’ resounded through the caverns of her mind as the biting gusts of winter twisted and broke stems, all that impermanent beauty dropping to the earth.

END

[1] A traditional Japanese gate most commonly found at the entrance of or within a Shinto shrine

[2] The Temple of the Golden Pavilion

[3]The Temple of Great Virtue

[4]A sub-temple of Daitoku-ji

[5] Literally translated as red leaves, often used to refer to the annual viewing of autumn foliage