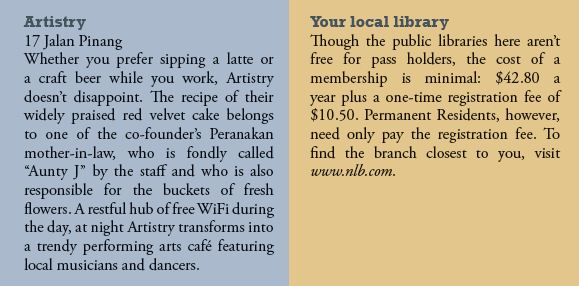

Published on September 3, 2013 in Young & Global Magazine:

Arch of Reunification

On an overcast afternoon in August, I stood on the upper balcony of Panmungak, the main North Korean building in the Joint Security Area (JSA) of the Korean Demilitarized Zone (DMZ), gazing over narrow, blue buildings. Dead center between Panmungak and the South Korean building called the Freedom House Pagoda, I could see the thick line of concrete that splits the two Koreas. Though we were a mere 70 kilometers from Seoul, it felt like we were on another planet.

Miss Choi, our tour guide, appeared at my elbow. She was a curvy North Korean woman in her thirties, but beyond that I won’t describe her or provide her real name lest I unwittingly get her into trouble. With a placid smile on her face, she led our group down the stairs, out of Panmungak, and across the quiet compound to the squat cyan buildings.

The JSA is used by the two Koreas for diplomatic engagements, but on that day it was devoid of life, save for stiff soldiers and nonchalant sparrows. Since visitors are forbidden from interacting with tourists from the other side, the area operates on something of a timeshare. As we explored the sparse negotiation space that sat squarely on the demarcation line, Miss Choi recited historic moments and explained that the main obstacle to the reunification of the Korean peninsula was the posting of American troops at the DMZ.

“Our country is divided. But maybe one day soon you can have breakfast in Pyongyang, lunch in Kaesong, and dinner in Seoul,” she finished wistfully.

The members of our tour group glanced at each other, but no one moved to put forth a conflicting opinion. Two days earlier, in the Beijing airport, a representative from Koryo Tours had warned us to expect such discrepancies. North Koreans have a genuine pride in their country, he had explained, and though they know Westerners have different versions of their country’s history, they simply believe we’re lying. Or ignorant. After all, why would our version of history be truer than what they’ve been told their whole lives? Would you believe a North Korean who told you Abraham Lincoln was a Nazi?

It was in Beijing—one of only four airports in the world that can fly you to North Korea—where I had first met the small group of adventurous travelers who would be my companions on this trip. I knew nothing about these people except that they were expats working in Singapore, and their curiosity about North Korea matched my own. It must, because we would be among only 3,000 or 4,000 non-Chinese tourists to visit the reclusive nation that year. For me, although I had moved to Singapore a mere five days earlier to reunite with my fiancé after a six-month separation, I was curious enough to take this trip he had planned, even if wasn’t quite the romantic reunion vacation I was expecting.

The representative from Koryo Tours had also given us guidelines for our visit. We were not allowed to photograph construction sites or people, and we were forbidden from wandering away from our guide. While it wasn’t impossible to sneak photos or creep off to out-of-bounds areas, Miss Choi had the power to restrict the planned activities for our trip if she judged our group to be unruly. Most importantly, later she would be the one to pay for any and all of our misbehavior. So we mindfully asked whether pictures were permitted and followed her like quiet schoolchildren.

Freedom House Pagoda and Joint Security Area viewed from the DPRK side of the DMZ

A short drive from the DMZ, a military lookout point stood at the peak of a hill, which our secondhand tour bus struggled to climb. Inside the little building, a North Korean colonel in full uniform gave us a history lesson in front of a large painted map. He then gestured for us to follow him outside, where a row of telescopes allowed us to peer out at the peaceful, grassy landscape, riddled with silent landmines. Beyond a tiny wall marking the border, military bases flew South Korea’s flag. I only half-listened to the colonel’s stilted English; I was skeptical of the veracity of his facts and more interested in studying his appearance. With his large cap and swamp green military garb, he resembled a Chinese officer from the 1960s. I noticed that his bars of honor were actually a multicolored square of plastic, and I wondered if he had seen a picture of a decorated official and endeavored to appear equally important. Affixed directly above this facsimile was a red, flag-shaped pin that featured Kim Il Sung’s smiling face.

Every adult I had seen in North Korea sported this red pin on his or her left breast, sometimes accompanied by a second red pin featuring the image of Kim Jong-il. Miss Choi said the pins were worn simply out of a desire to show respect; there was no mention of compulsion. However, I later learned that the law used to be: forget to wear your pin once, receive a warning; forget it a second time and face punishment.

Much like the colonel’s illusion of military honor, I discovered that the nearby city of Kaesong was also designed to appear more than it was. Houses of solid concrete had brick patterns painted on their exteriors, and concrete walls sported motifs to mimic stone ones. Kaesong was the only city to change control from South to North Korea because of the Korean War. As such, it is the southernmost city in North Korea. Its name translates to “Triumph”, but it is a town of worn buildings and of families fractured by the 38th Parallel.

Atop a hill, a towering bronze figure of Kim Il Sung gazed down a steep road into the little city. Despite the fact that we arrived into Kaesong at 5:30pm and rush hour was in full swing, the streets were scantily populated. As we would for all dinners on the trip, we ate in a nice restaurant filled with only Western tourists, and it soon became apparent that the locals didn’t make a habit of eating out. We slept in a traditional inn, sleeping under mosquito nets in the heavy darkness of North Korea’s nightly nationwide blackout.

The following day, the drive from Kaesong to the capital of Pyongyang took two hours on Reunification Highway, which had no lane lines, but was peppered with guarded checkpoints. Except for the occasional truck or other tour bus, the highway was empty. Tunnels were devoid of lighting. Cornfields lined the road, as well as flat plains in all shades of green and brown merging into distant mountains. We passed tanned men and women on bicycles, brown cows tied up to graze, children bathing in shallow rivers. It’s easy to forget in such a strange country –especially one so ideologically at odds with the Western world – that people are just people everywhere.

A plush pink charm of the whole Korean peninsula swung from the bus’s rearview mirror as Miss Choi gave us lessons on her country’s history and culture. Once again I was struck not only by the bizarre interpretations of historical events but how much weight they still carried in the present. It seemed to me that the people of North Korea obsessively clung to past slights and lorded over past triumphs, while the rest of the world had long since moved on.

The history North Koreans tell is an idealistic, childlike version of the world. Their heroes are brave, their leaders compassionate and wise, their enemies evil and uncomplicated. The big questions have been answered unambiguously. But looking out over the serene landscape I wondered about the people starving somewhere hidden from view. Did they still love their country, their Eternal President, their Great General? Or was the illusion shattered? Were they heartbroken?

Before arriving in Pyongyang, we pulled over to admire the Arch of Reunification, which straddled the highway itself. The concrete monument consisted of two women in traditional Korean dress—one representing the North and the other the South—leaning forward to jointly uphold a sphere emblazoned with the complete land of Korea.

Looking at the Arch, I didn’t know where the future would take this inexplicable nation, but I knew it wouldn’t be to the joyous and peaceful reunification the North Koreans were convinced was imminent. I also knew that anything I said to the contrary would at best fall on deaf ears, and at worst endanger the safety of our sweet-natured tour guide, so I simply took a photograph of the monument before we moved on.